Responses edited for length and clarity

An earlier version of this article described composer Raven Chacon as Cherokee, which is incorrect. We apologize for this mistake, and have corrected it below.

Firstly, congratulations on the release of your debut album, 3BPM. I spent a good chunk of my morning listening to it and also reading what you have put out with the album, about the context and your inspirations. As I was listening to it, I kept thinking about my own perception of Wild Up as a really eclectic, loving family, as it has been for so long. What came across to me was the sense that you were saying, “I have enjoyed how music has guided and supported my family. Here’s a framework for you to do it with yours, how whatever that means to you.” What was it like to create and record the album with your Wild Up family?

Chris Rountree:Well, first of all, that’s totally, exactly it. I’m so glad that has come across in that way, and that was legible. You know, there’s this thing about going through conservatory, where so much of our learning is fully top-down… There’s a big thing about lineage, feeling right and wrong, feeling moral and ethical. So, we come out of conservatory with so much pressure on us.

I don’t really know a classical musician that is not kind of broken from going through conservatory.

I saw some meme the other day that was some violinist who was interviewing people randomly on her Insta and TikTok feed, and she would ask every classical musician, “What are your hobbies?” with the mic in their faces. They were all, like, “huh?” This thing about following a certain lineage becomes so powerful that our internal judge becomes really loud. For whatever reason, as I’ve gone through my career, I’ve been more and more and more interested in pieces of music that get the judge to be quiet.

I don’t know how that happened. Early on, when we were putting out [a piece], some copy said my name, and then in the crediting, the word “conductor,” with a question mark. I went to conducting school, and it was very painful. And I love conducting. It’s my favorite thing, to conduct major orchestras every day.

And yet, that lineage is built to punish your brain. [Wild Up has] grown into this thing that’s much more amorphous and much more non-hierarchical. We’re leaning toward pieces that cause democratic, dialogue-based, or intersectional processes and frameworks. I started composing because I had ideas for Wild Up that nobody else was doing. When I started writing music ten or fifteen years ago, it was all notated. It was not a framework for people to have a more grassroots experience of their own agency. Now, I’m really only interested in making something that truly is a framework for shared experience and a framework for dialogue. And I really can’t imagine making something that’s not that.

DLAR: It’s really well executed, and I see that coming through very well. There’s a similar attitude in this album, I think, to Darkness Sounding — we want people to see joy and a deliberate nature when it comes to gathering. Maybe that’s an overused word, where people say, “Oh, we’re gathering.” Like that’s just supposed to be significant, somehow. The follow-through is what makes it different to me, that Wild Up has committed for a number of years to doing Darkness Sounding, to engaging in these really human rituals and conversations, and philosophical discussions that also have a spiritual nature. Is there a particular feeling that kind of arises in you when you’re in that environment with other people?

CR: I don’t know even how to name it. Actors have a name for it, which they call “rasa,” or “the taste of the room.” Both my parents were directors, and my mom told me a story about when she was watching the Olympic Arts Festival in 1984, which I guess I was also watching because I was born in 1983. I imagine I saw some of that.

There was a Japanese theater troupe, and they all laid down flat as they entered the stage, and they prayed to the stage as they walked across the threshold. So many performers hold this energy as they enter a space. As I’ve built Wild Up’s practice, it’s extending that taste of the room fully to the experience of the audience and centering their experience. In Brahms’ memoir, he says, “I always sleep. I always stay in a box for a concert. I won’t go to a concert unless I’m sitting in a box, because then I couldn’t sleep through it on a sofa. I want to talk to my friends about how judgmental I am about all of this, and I can’t do it while I’m sitting next to other people.”

In Berlioz’s memoir, he’s like, “There’s a specific concert that I hated.” (Also, I’m talking about composers from that era because we think of them as quite pristine). Berlioz says, “I hated this concert, and I knew I would hate it, so I brought extra oranges.” So, first of all, we read they were always eating at concerts, which means they were talking in the seats. And they were sharing oranges. He said, “I brought extra oranges so I could tell everybody how I hated the concert while it was happening in the hall, while I gave them oranges, because the oranges were very good, in the context of being better than the work.”

I’m not saying everybody should, pardon me, talk sh*t and eat oranges at our shows. However, it’s a cool idea, that everyone should be able to have their own experience of the thing and find their own way in. We should think about how many possible ways we can give them.

We tend to have more time to rehearse than anywhere else that I work. We build a lot of time for dialogue, and our executive director [Elizabeth Cline] and I are really focused on artist wellbeing. We’re actively taking care of the artists so that we can put them in situations with the audience that are perhaps abnormal, so that we can make more space for the audience experience when we’re performing. For us, there’s a spiritual journey that takes place in the rehearsal room. That is the sacred space. Church was Wednesday, and this is just a Saturday.

Do you feel that it’s possible to preserve that ease and dynamic even when you’re doing an open rehearsal? I’m thinking about Democracy Sessions, and the fact that it’s an open rehearsal process. How does that go when you have people there witnessing what you and the group are doing?

CR: Sometimes it goes great, sometimes it goes really bad. There’s a vulnerability there where some people, particularly worse-mannered people take up a lot of extra space. We had somebody heckle us in Toronto, which we had not had before, and it was amazing! We played a piece of Raven Chacon’s, so we set the stage for the heckling very well. For that reason, it was not unexpected, even if I didn’t like this response.

This piece is called Whistle Quartet. There were twelve people in the band, so we did it as little pods of three. We got tickets for the concert, so we came to our own concert as an audience. The stage was empty. They gave a land acknowledgment, as they do in Canada, and we’re playing a Diné (Navajo) composer’s work. The light goes up on stage, the light goes down in the hall, and we begin playing dog whistles in a quartet. Of course, a dog whistle… Raven wrote the piece about racism.

It’s so quiet, the dog whistle. A dog would freak out, but for us, it’s so quiet, and [the melody is] passed around the room until all twelve of us are playing, and you hear the same contour. It kind of lilts and falls off each time, so it has this kind of aspirational quality at the beginning, and then a cascading into some kind of inertia or loss of momentum. We play for about five minutes, and it’s very quiet, but it is audible. People start to look around, and then one by one, we stand up. We move to the stage because then we go into a big drone piece of Julius Eastman, and we dovetail both pieces on top of each other.

As people are starting to move to the stage, some guy screams; “Where’s the music?” At first, I thought maybe he was hard of hearing, but then he seemed to yell something else, and then people applauded after he screamed it. Did this person research the show and come to make a racist gesture on top of the work of a Native composer? Or were they just provoked by not understanding?

Raven’s pieces are supposed to provoke. They’re really provocative on purpose. They’re supposed to be painful, and it certainly was. We told Raven about this, and he was thrilled. My string players were so pissed. We proceeded to play the angriest concert in our organization’s history because everyone was so mad. There were some people in the front row who were talking the whole time — they had young kids, and they were just chatting to the kids the whole time, the whole show.

The thing is, if we’re trying to make a space where the rules are subtly different or where we’re engendering a different type of listening, sometimes it goes to a strange place. We were playing a piece of Julius Eastman at the end called Gay Guerilla. It’s Eastman’s only piece with a pulse that is fully set and you play the pulse the entire time. We thought we were going to set the stage for Gay Guerilla for sixty minutes, and then we’d take this big spiritual journey for the last thirty minutes together… regardless, it was amazing. The standing ovation was bonkers in Toronto. They were thrilled. I mean, we’ve never had an ovation like that before, but it’s because the audience had been so provoked. That’s the risk.

This summer, we saw the release of the fourth Eastman record in four years. Incredible consistency, and a lot of investment on the part of the group. Staying with one composer for this long, seeing the work develop, and having the records come out. Was there anything that surprised you along the way? Anything that developed from the beginning to the end that was unexpected?

CR: Every single one of the albums just had a different kind of way of going toward the work. For example, Vol. 3 is “If You’re So Smart, Why Aren’t You Rich?” He wrote these cluster chords going up in chromatic harmony, and he wrote it around at the dinner table. That third record was focused on endeavoring, and pain. But in the studio, we really don’t want to fail, and [the instruction] is “go until failure.” And we don’t know what the Eastman score looked like, but we hear what it is, and we made the score afterward! I’ve been really thrilled that every single record has shown a different aspect of Julius’ work, that we’re not just doing the big minimalist pieces, but also some of the romanticism and some of the modern-postmodern work. The big surprises are probably about the dialogue and the time it takes to make these. I expected this to happen, so it’s not really surprising, but it has fully transformed our entire practice. The way I’ve described this many times is through Pina Bausch’s dance company. Before Pina Bausch got there, they did repertoire, and then she got there, and now they only do her work forever.

That’s crazy. That’s insane. I feel like in our encounter with Eastman, we got a new band leader. What [the pieces] are and what they demand of you is so significant that our encounter with this work has just utterly changed our practice. I don’t know if we’re going to go back. I don’t think we’re making anything like before.

Is that scary, at all?

CR: I think the scary things about it are personal. What’s not scary is the work feels really meaningful, there’s tons of joy around the work. My worries are that there’s not that much work like this work. I don’t know how to find the things that will fill my heart in the same way. There are so many good things, and I like so much music in the world, but not all that fills my heart in this way.

I’m really looking for a very specific thing. I can list fifty composers that I think fall into that thing. Most of them don’t write classical music. So, suddenly there’s a question about all of my personal training — perhaps I’m not a classical musician! That is really scary. Simultaneously, one of the reasons why the Eastman project has worked so well is that it’s been a huge part of my practice to center other folks who are not me. I feel pretty good at locating other folks in the light. When I’m personally doing a project that diminishes my involvement, and that should diminish my involvement, that attention changes. I’m always going to champion this work, but I can’t be in all of it.

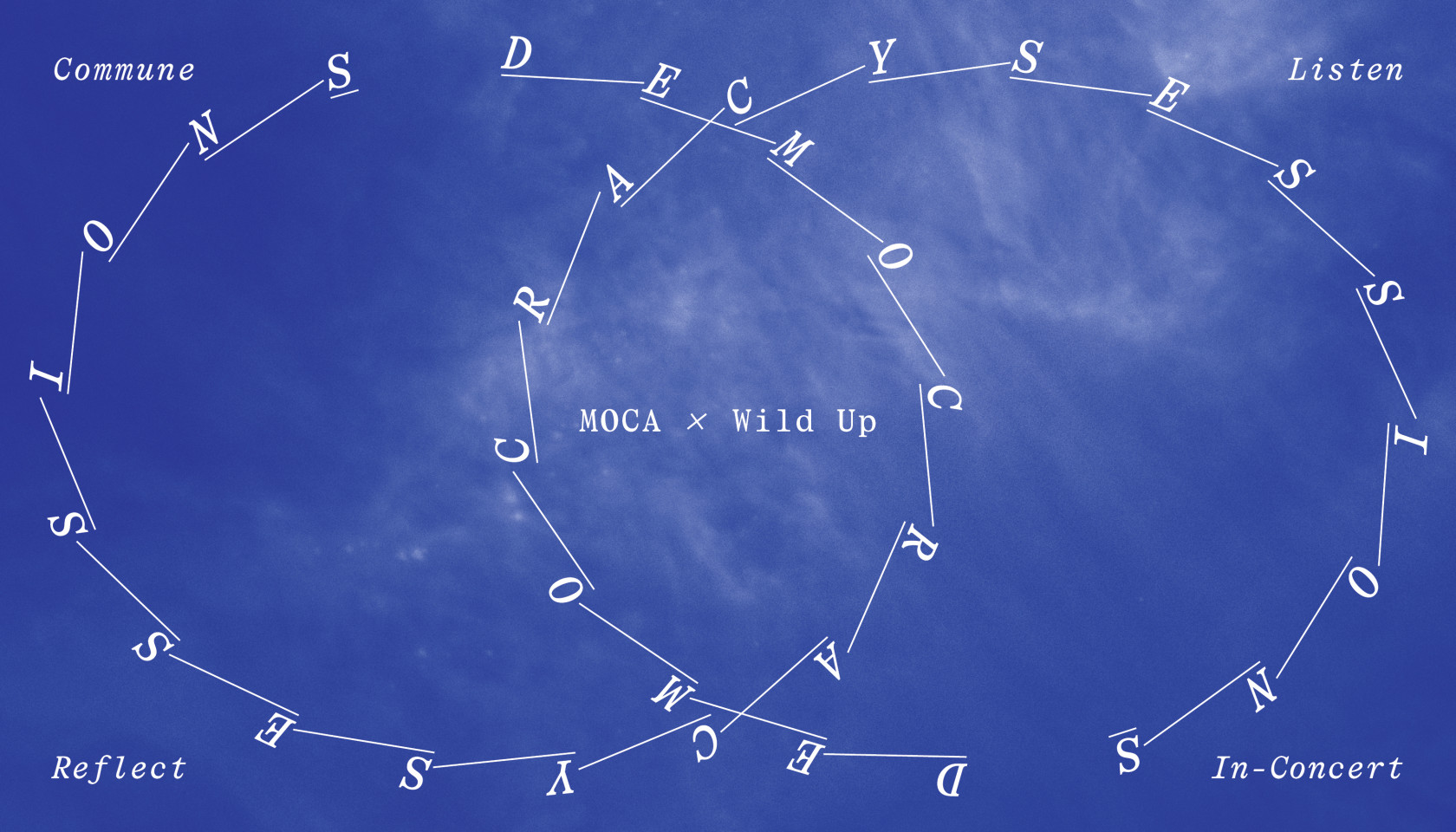

In a couple of weeks, you’re partnering with MOCA to do a three-day series of Democracy Sessions. By the time people read this, the event will have happened, and the election will have happened. Does the outcome of the presidential election affect what you are trying to offer audiences at this event, or is it simply about community care?

CR: I have lots of questions about whether music can have direct political action in it and about the good that art can do in the context of big systems of power. I also think that there’s no such thing as apolitical music. That’s been a bedrock from which all of our programming flows, for sure. In a certain way, every concert we do is Democracy Sessions. How I feel politically is irrelevant — what is really relevant is making a space where people can feel, and where people could be together when they’re likely to want to just like, watch TV and order a bunch of takeout and just like get super wasted.

That’s what I’d be doing, that’s cool. But also, what if we spent that time together? And what if we have some kind of dialogue and also some subtle dialogue? And also, are there different ways that people could participate so that they can get into their bodies? We have all sorts of different programming planned for that weekend, from the transcendental Stockhausen piece called Stimmung, one of the first pieces of drone music in the late 20th century, to a devised piece made using the audience’s questions.

Audiences will be asked questions the whole weekend. There’ll be a big board where we collect all the audience text. The theater and music and dance performers will all be devising a show using that text as the libretto. There will be a reading from Ted [Hearne] and Chana [Porter]’s new opera, The Dispossessed, and an experimental audio archive project by Harmony Holiday, using the speeches of Kamala Harris and an interview with Nina Simone’s granddaughter.

We’re feeling good about it. We had a big skull and crossbones in our calendar for months, like, “Don’t do anything!” MOCA, our partners in this, also had something similar. A big red brick in their calendar. Once we learned that, it was like… “Doesn’t that mean we should be doing something, then?”